This blog post was originally published by Border Criminologies.

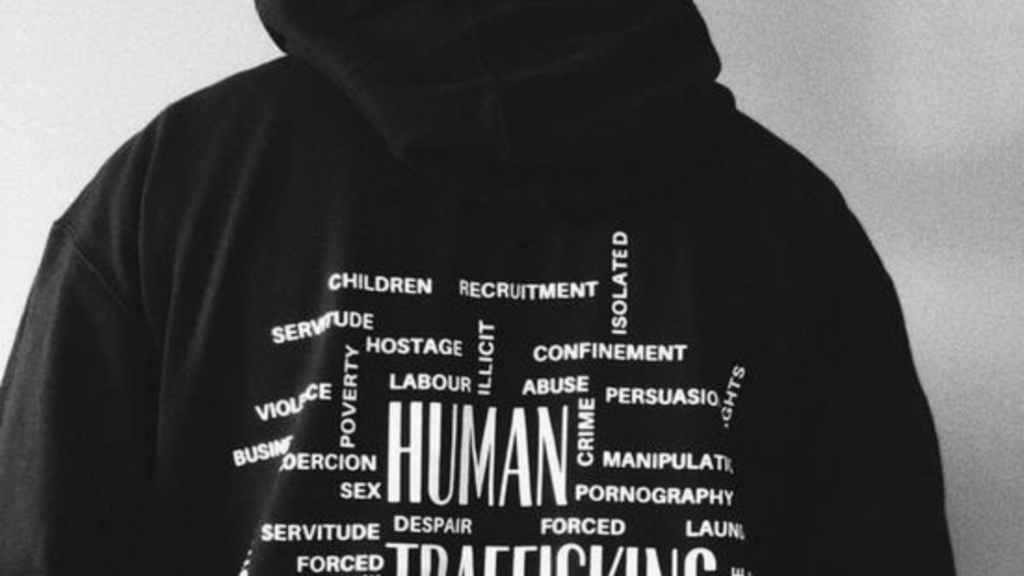

In September 2019, the Parliamentary Secretariat for Reforms, Citizenship and Simplification of Administrative Processes within the Office of the Prime Minister of Malta issued a public consultation document on sex work and trafficking, inviting submissions from experts, academics, civil society organisations and other interested parties. Over the past few years, the reform, which seeks to develop a comprehensive National Strategy Against Human Trafficking and decriminalise the sex industry in a bid “to protect vulnerable people from being exploited as sex workers and at the same time further enhance the fight against trafficking of persons”, has sparked a flurry of debate. Two main camps, mirroring the entrenched schism within activism, policy and academia, have emerged. An abolitionist contingent, maintaining that sex work is a product of a patriarchal social structure and intrinsically exploitative; and a pro-sex work movement, positing that sex work is work and can be wilfully chosen as a means to make a living. According to abolitionists, sex work and trafficking are cut from the same cloth – by quashing the sex trade, human trafficking will cease. Abolitionists reject the decriminalisation of the sex industry – a measure favoured by the pro sex work movement – as an unseemly legitimation of the abuse of women, and call for the criminalisation of the buyers of sex services, otherwise known as Nordic/Swedish model.

Drawing on recent media reports, this post critically explores the main arguments made by Maltese abolitionists opposing the reform. In particular, it problematizes representations of sex work as trafficking and of trafficking as sex trafficking and raises the question: What are the implications of these conflations and could they do more harm than good?

Whose opinion matters most? Hierarchies of credibility and issue framing

At the heart of a majority of media reports is the standpoint put forth by the Coalition on Human Trafficking and Prostitution, a group of NGOs, academics and other professionals, spearheaded by several renowned women’s rights activists. Among the Coalition’s chief concerns is the dearth of expertise within the technical committee tasked with developing the legal framework for the reform, which comprises a range of professionals specialised in LGTBQ rights, disability, sexology and more. Cautionary warnings about the committee being “devoid of experts in this specific area”, excluding stakeholders “who work directly with sex workers” and ignoring “the experienced advice which these 46 + NGOs have put forward” are a common refrain. The problem is not merely personal, but also ideological: in the eyes of Coalition representatives, lack of knowledge about sexual violence against women renders committee members unfit to pronounce themselves on matters pertaining to sex work and trafficking. This exclusionary discourse helps manufacture hierarchies of credibility, where the label “expert” serves the purpose of cementing legitimacy. Highly reminiscent of these dynamics is FitzGerald’s and McGarry’s (2016) description of the Irish campaign for Swedish-style laws, where TORL (Turn Off the Red Light) activists called upon “experts” to buttress their claims in favour of the criminalisation of the purchase of sexual services.

With sex work depicted as inherently misogynistic and exploitative, “a vicious parasite that embeds itself in the fabric of society” and a trap for poor and vulnerable migrant women, it comes as no surprise that those considered to be the real (and only?) experts are activists on the frontline of the battle for gender equality. The point here is not to refute the existence of violence and abuse in the sex trade, nor deny that there are women, transgendered people and men who are trafficked into the industry, rather to question the narrow representation of sex work as a form of violence against women (VAW). By subsuming sex work under the broad umbrella of VAW, abolitionists lend weight to their claims; concurrently, by construing sex work as a gender equality issue affecting all women in view of the fact that they are women, they render it more palatable and relatable. In so doing, they flatten existing class, race and migration-related differences. Black feminism, critical race scholarship and critical approaches to trafficking bear witness to the harms of this blanket approach, which silences a multiplicity of voices and experiences, ignores the distinct challenges faced by migrant and minority women, and effectively perpetuates White Saviourism and rescue mentality. Moreover, when all sex work is viewed as violence, abuse is watered down – rape, psychological and physical violence become occupational hazards and scant attention is paid to the circumstances and factors that expose sex workers to enhanced dangers.

Claiming that all sex work is sexual exploitation and therefore violence against women, and relatedly, that migration for involvement in the sex trade coincides with sex trafficking and forced prostitution, is both inaccurate and dangerous. Painting women as mere pawns in the hands of ruthless (male) traffickers and in dire need of protection, does a great disservice to women and paradoxically detracts from the feminist battle for equality. It reinforces dominant constructions of women as innocent, weak and helpless, and misconstrued views of masculinity as essentially resilient, overshadowing the numerous challenges faced by migrant men and transgendered people working in the sex industry. As a result, “fallen women” who do not fit neatly into the box of ideal victims and men who may, in fact, be the targets of exploitation, are excluded from assistance and protection.

Conflating human trafficking with sex trafficking entails turning a blind eye to the exploitative labour conditions faced by many migrants who work in other sectors. Perhaps even more worryingly, this approach relies on a law-and-order agenda hinging on the State’s support. It therefore encourages more stringent border control, as well as large-scale policing of migrant women and the sex trade as a whole, driving undocumented migrants underground, fuelling their marginalisation and enhancing their vulnerabilities.

Moral panics and border management

Unless the government changes its course, Malta’s future is grim, abolitionist activists insist. Decriminalising sex work will convert the island into a “ European Thailand” and “ sex tourism mecca”. This quasi-apocalyptic scenario and the sensationalist language used to conjure it, is reminiscent of the moral panics underpinning many abolitionist and anti-trafficking campaigns worldwide. Time and again, opponents of decriminalisation in Malta evoke the daunting prospect of a country in complete disarray. Parents are urged to stop and consider whether they truly wish for “six-foot anti-prostitute fences [to be built] around schools like they did in Berlin”, or “prostitution [to be] promoted in schools as a legitimate career choice, and advertised in broad daylight as an acceptable avenue for young women and girls”. The dangers of moral decay within Maltese society are routinely evoked in an attempt to bring people together against sex trafficking.

Alongside trafficking for sexual exploitation literally exploding, Coalition representatives ominously predict that organised crime, drug trade, sexual violence and other will also proliferate. This militaristic language raises the chilling spectre of a nation at war, whose borders need defending. As Segrave (2009) observes, although the border undergirds trafficking discourse, it is often an unquestioned concept. By problematising Malta’s inability to ensure the “high levels of effective monitoring and enforcement” required to tame the predicted chaos sparked by decriminalisation, abolitionist activists construct the Swedish/Nordic model as the only viable solution to guarantee national safety and security for all. This despite many sex workers – who in actual fact ought to be recognised as the “real experts” in the matter – speaking up about the harmful effects of the Swedish approach on vulnerability to violence and abuse. It is difficult to fathom how anybody could possibly grasp the peculiarities of the legal models of sex work in place in different countries around the world, without engaging in conversation with those whose lives they affect in the first place: men and women, migrants and locals, who work in the sex trade or have exited the industry.

As Coalition representatives continue to insist on the inherently exploitative nature of sex work, the debate, couched in questions of choice vs. coercion and agency vs. exploitation, goes around in circles. In the meantime, migration, labour and socio-economic issues lurk in the shadows, unwelcome guests at the dinner party. Yet if the overarching aim of reforming legislation is to bolster the protection of migrant and local sex workers, and victim/survivors of trafficking, ignoring barriers to mobility, labour conditions and the state’s overall responsibility in fuelling exploitation, surely does not do any good. In all likelihood, it does more harm than good.

The views expressed herein are my own and do not reflect the position of Leiden University.